Mothballs in Aspic

Minnie and I rarely leave home in the winter, but if we do we make a spectacle of our sweaters and coats, contrasting the black ice and the chalky sky with scarves from Istanbul, emerald green weaves from Donegal, squash-colored berets and mitten hats, and yellow or lavender longcoats purchased from hippies at the pier. And we appear at some generous brownstone stoop in the middle of a blizzard and magically produce Moorish tagines and crocks of home-made honey mead once we're welcomed inside. Recently, on just such an evening, we visited the home of our dear friends Kevin West and Earl Ray Saathoff. The wind and snow were whirling round us like spirits as we rang the doorbell at the most luxurious hour of 9 p.m. If people want you around, you can tell when visiting at 9 p.m. They're past all politeness by then. Either they want for company or they don't. Minnie and I would rather laugh loudly and walk away at the slightest hint of a grimace than be met with incertitude or polite good manners. At 9 p.m., you can tell what's what and act accordingly.

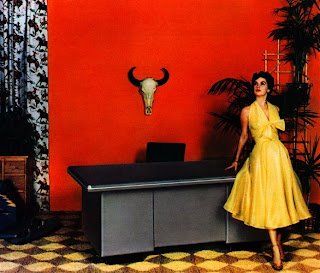

Earl and Kevin are filmmakers and Minnie and I have known them for years. People of our bent have decorated our flats the same way since we recovered from Art Nouveau and fin-de-siecle flourishes after World War I. You'll always find a field of gilt-framed, half-sketched Adonises in the foyer, stairstepping down from the high pressed-tin ceilings. As you hang your cloaks and scarves on the gnomish talons of coat trees you'll look down the foyer to a window, naively showing the best of a city turned drowsy with winter -- a haloed streetlamp, luxury cars parked akimbo in glad confusion, a fire escape light that gives each falling fleck of snow its ornate and delicate due. And the apartment will open up to you beyond the foyer and surprise you with its lack of substance. No more spirit balls tucked behind porcelain dolls propped up on a stack of antique talking boards. No more Victorian terrariums glowing with every kind of marsh moss, lined up like easy prey beneath the mythic wingspans of skulking stuffed hawks, falcons and vultures. We moderns deplore too many easy shadows.

Instead, there are the requisite implacable African gods, long ebony faces with blanks for eyes and puckered blanks for mouths, each orifice stretched in warrior rigor. And there is a long, fleet Zenith Hi-Fi beneath the picture window, so the masters of the house can watch themselves in the glass as they slide rare 78 rpm records from rice paper sleeve and set the diamond needle down onto these Congolese stomps, tunes from ancient Harlem sheathed in purple velvet, absinthe and opium. Earl is wearing a red turtle-neck sweater tucked into gray work slacks and Kevin is at the bar cart situated, for now, in the center of the room. He's imitating the sounds of ice cubes hitting the bottom of the glass -- "plop," "pock," "pop". They're glad for visitors and we could tell if they weren't. We only visit by surprise. It's a dank parody of the old fable, where each person must feed or water a stranger in fear of that person actually being a god. In our group, it makes us bold when visiting. We ask for more than that to which we'd be entitled, we make ourselves splendidly at home. There is no question that we are gods.

I love watching Kevin make this ice-on-glass sound with his tongue against his teeth. I love his grin as he does it because it's not much of a talent. And then he makes a glug-glug sound as he pours whiskey into one glass, wine into the other, mead into mine (though mead slips into a glass the way a spider slips between satin sheets), etc. Drafts make the main room daft with wavering candle flames and the artificially flickering amber electric lights in the sconces on either side of the fireplace add some wit to the cliche. We are not, all of us, candle worshipers. In fact, in New Orleans, there is a shop that sells the most marvelous lightbulbs, ones with strange porcelain Passion Play filaments, so you can watch the electricity quiver blue over miniatures of the crucifixion or quiver red over Judas' betrayal of the Christ. You can get lost in these as easily as into a candle flame.

But regardless, our kind have tidied up our act some since the turn of the century. Our books are no longer moldy, our clothes no longer smell of last year's rainwater, and our art no longer requires an intense squint under an eyeglass to divine its purpose. We have entered, along with all elegant folk, the era of the clean line. And in case you think that has broken the mood, or sold out to modern convention, I ask you to take a look at the home of Kevin West and Earl Ray Saathoff, on the Lower East Side, just on the border of our city's Chinatown.

They have managed to balance the sinister and the cordial perfectly. It would take an unsuspecting guest at least three drinks to notice that the Calvary crosses lit by the quivering blue lightbulb filament are turned upside down, or that the straw skirts around some Haitian fetishes (one Senator asked if they were fishing lures), rustle of their own volition, or that the walls themselves veer slightly inward near the pressed-tin ceilings. Each of the very large African masks are lit from within by very small red Christmas lights which appear more and more infernal the more wine you've consumed. Among the usual, relatively tame, framed erotic photographs from the fin-de-siecle, there are a few that will dizzy you if you allow yourself a panoramic view of the flat. There is one tin-type of a deceased infant, propped up in his coffin, between his two smiling parents that will send a shiver to your core if your eye simply stumbles upon it. They hired the photographer two days before the child succumbed to Yellow Fever and they tried valiantly to incorporate the happiness of their new family with the grief over the child's death. If you look closely, you'll see how their smiles are forced and if you look even more closely, you'll see that the infant's smile is the result of a set of tinsel-covered clothes pins attached just above its ears, lifting the lifeless cheeks. Some items in the room have an undertow and I'd be lying if I said I didn't get some glee over watching strangers succumb, slowly, to dread, or, at the very least, a modicum of discomfort.

But, as we here are all close friends, both Minnie and I tick off these details with familiar delight and go on about our conversation with Kevin and Earl. Some film scholars will be coming over later to talk about something we all find fantastic! Apparently there are esoteric, occult chapters that were excised by philistine publishers from many of the most scholarly texts on 20th Century experimental film. Minnie and I are immediately fascinated. Our cocktail friends are to include a compatriot of the great archivist/Magus Harry Smith, the great Amos Vogel (Film As a Subversive Art, 1974), P. Adams Sitney (Visionary Film, 1974), and Maya Deren's half-brother, Sidney Acollat.

It is well-known that the purpose of many experimental films -- Kenneth Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome and Invocation of My Demon Brother, many of Harry Smith's Early Abstractions, the films of Joseph Cornell -- is incantatory. In other words, they sit still for no one. They are spells, plain and simple. It takes very little derangement of the senses (two cups of wine, a little marijuana, a sliver of blotter LSD, a slight pillar of hash), for Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome to become a very different film with each viewing. I remember a friend of mine (I'll call him Akadman), who assured me that, after drinking several huge gulps from a box of wine, the content of Inauguration was vastly different when he was looking at it in a full-length mirror than it was when he actually faced the screen. There were long chapters on this in the books by Vogel and Sitney, but the publishers would have no part of it, and demanded those portions of the book be removed. There is not a soul in our particular crowd who does not find that laughable. We've all seen certain of these films as transmissions, vessels, haunted media, for ages, but apparently there may be a gathering this evening of specialists.

Minnie and I feel honored. Truly honored. I remember many years ago, at Cinema 16 -- I don't recall the year exactly, but it was probably the early 1950s -- seeing some Kenneth Anger films and feeling as if they were organic, not at all tied to the screen or even the projector, instead living on their own in a strange field between. They could change and adapt based on the mindset of the viewer. It was fine to know that I wasn't going mad. Both Kevin and Earl laughed at that, being film buffs and well-educated in the arcana of that particular artform. The wine and the mead and the martinis have warmed us into a variable state. We are ready for the conversation. I can see it especially in Minnie's small, pinched face. She is so prepared to be eminently fascinated by the new guests. The African masks are glowing red from within, the infant's rictus and dead stare are ignited by the fluorescing filaments of the blasphemous Calvary bulbs, and the guests are arriving.

Comments

Post a Comment